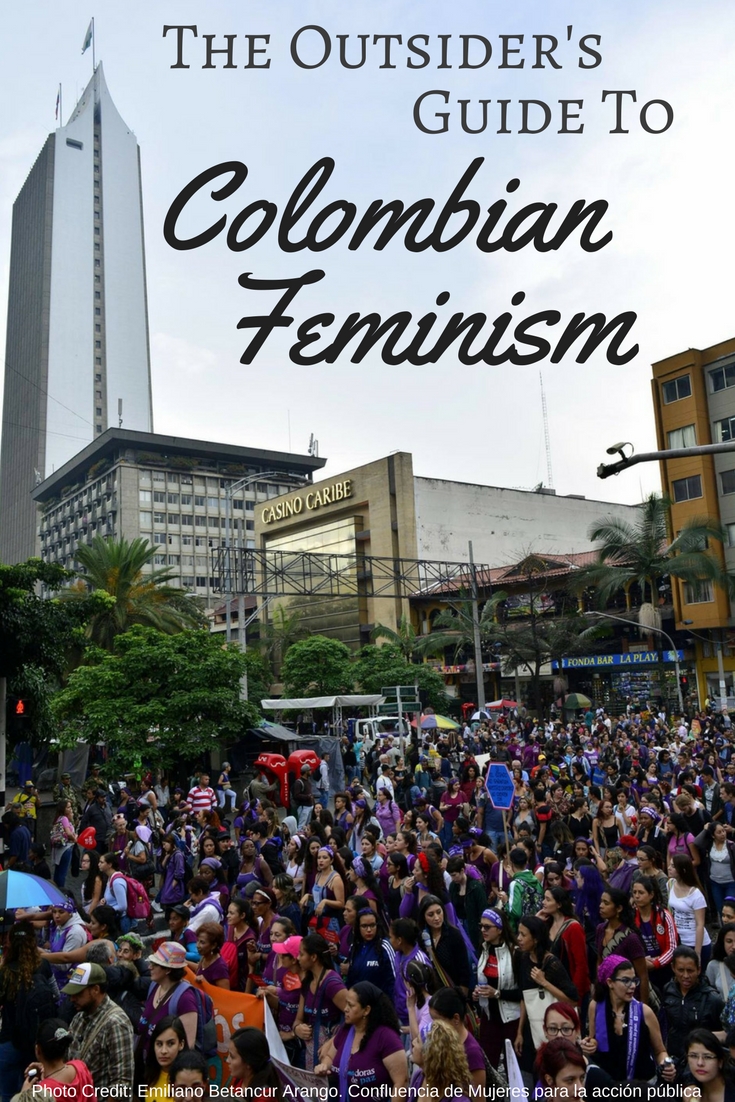

Protesters move through Medellin streets on March 8, 2017

*All photos are credited to: Emiliano Betancur Arango. Confluencia de Mujeres para la acción pública. Thank you to Confluencia de Mujeres Antioquia for the use of your fantastic photos!

On March 8th, 2017 in Medellin, Colombia, it rained all morning with no sign of stopping. I arrived at the iconic Plaza Botero at 2:00 with my shoes already wet and an umbrella in hand, and made my way over to the growing mass of purple-clad protesters. Obviously, a little bit of rain wasn’t going to stop Medellin’s women in their fight for liberation on International Women’s Day.

Speakers at the tribunal

Although it is a day of celebration of the accomplishments and triumphs of women worldwide, International Women’s Day is also a day in which we can analyze the inequalities that exist for women around the world, and mobilize in attempt to raise awareness and bridge those inequalities. There were marches planned in cities around the globe, including many major cities throughout Colombia. Worldwide, women protested injustices such as gendered violence and the gender pay gap (because yes, even in 2017 women still earn less money than men for equal work, around the globe). It just so happened that I was in Medellin on March 8th, and it seemed only fitting that I spend the day marching in solidarity with the women and humans of Medellin.

The agenda for the day consisted of a tribunal (essentially a panel discussion of various feminist issues in Colombia, as presented by a variety of speakers), followed by a march from Plaza Botero to Plaza Cisneros in the city center. When I arrived at Plaza Botero for the start of the tribunal, there were a few hundred people starting to congregate, the majority of whom were dressed in purple with t-shirts, headbands, and decorated aprons touting feminist slogans, denouncing structural violence.

As a feminist from the United States, my observations are limited when it comes to understanding the complex socio-political systems at play in Colombia and how these systems impact women’s rights. However, my time at the protest helped me greater comprehend some important aspects of Colombian and Latin American feminism. As such, I put together this glossary/guide for outsiders to the Colombian feminist movement who are looking to learn more. Hope it helps!

Rally attendees in purple aprons, denouncing patriarchal violence

Important concepts, definitions, and hashtags in Colombian feminism

“Ni del Estado, ni de la iglesia, mi cuerpo es mio” (Neither the State’s nor the Church’s, my body is mine)

The discussion topics during the tribunal, as well as the signs and chants at the rally, were indicative of the pervasive issues facing Colombia in its fight for gender equality. Some topics discussed include: Colombian politics and representation of women and women’s issues in government and legislature; reproductive justice, including access to birth control, safe abortion, and sex education; sexual violence in Colombia, specifically violence against women; the gender pay gap; homophobia and LGBTQIA+ representation; intersections of race and class in the fight for women’s rights in Colombia; femicide (see below); and violence against women as a result of the armed conflict in Colombia (see below); among others.

Potential trigger warning for the following sections, due to discussions of sexual assault and gender-based violence.

Paro Internacional / Nosotras Paramos

International Women’s Day saw events in countries throughout the globe. This year’s theme? International Women’s Strike (Paro Internacional, in Spanish). Generally, the strikes called for women to take the day off from (paid and unpaid) labor, as well as purchasing. The strike was inspired by historical events in Iceland and Poland, in which women suspended work in protest of unequal pay (Iceland) and planned legislature that would criminalize abortion and miscarraige (Poland). This year’s strike was designed to follow in the footsteps of these strikes, to show the world that women have a huge impact socially and economically, and that woman deserve to be fairly compensated for their work and deserve to live in a violence-free world.

More than 50 countries participated in the International Women’s Strike. In Colombia, there were events in many major cities, including Medellin, Bogotá, Cali, Cartagena, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, Manizales, and more. The moniker “nosotras paramos” (#nosotrasparamos), meaning “we stop” or “we strike”, was used in feminist spaces throughout the country to show participation in the strike.

An article published in Lanzas y Letras summarizes the motivations for the strike in Colombia as follows:

Los movimientos feministas y organizaciones de mujeres promueven y se suman al Paro Internacional de Mujeres el 8 de marzo. Se espera que la movilización, la desobediencia civil, los plantones, las actividades artísticas, y todo tipo de manifestación de digna rebeldía, sean protagonistas en esta jornada de manifestación mundial. Se apuesta a que las mujeres hagan un alto en sus labores diarias, para salir a las calles y parques, para incomodar al acomodado, para decirle a los civiles y militares que los cuerpos de las mujeres no serán más un botín de guerra, ni en tiempos de conflicto ni en tiempos una paz que aún está por verse; que las lideresas jamás serán tocadas, que el Estado será quien responda por su protección y que el trabajo de las mujeres jamás sufrirá subordinaciones salariales.

This translates to: “Feminist movements and women’s organizations promote and join the International Women’s Strike on March 8th. The mobilization, civil disobedience, blockades, artistic activities, and any type of protest in dignified rebellion should be at the forefront of this day of global protest. It is expected that women will suspend their everyday labors to take to the streets and parks, to make the comfortable uncomfortable, to say to all civilians and military personnel that women’s bodies will no longer be considered spoils of war, neither in times of conflict nor in times of peace (which still remains to be seen); that the female leaders will never be touched, that the State will protect them and that women’s work will never suffer from unjust salaries.”

Rally in full swing in Medellin on March 8th

Feminicidio

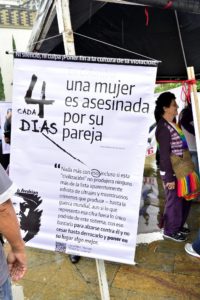

“En Colombia, cada 4 días una mujer es asesinada por su pareja” (In Colombia, every 4 days a woman is killed by her partner)

One fundamental concept that came up throughout the day, during the tribunal and the march, was the concept of feminicidio. Feminicidio (femicide, in English) refers to the killing of a woman or girl, due to her gender. It’s an important term that is used in feminist spaces not just in Colombia, but throughout Latin America.

One might wonder, why not just call it homocide? After all, murder is murder. However, the use of the word feminicidio is actually very effective. The naming of feminicidio as opposed to homocide allows us to consider the violent patriarchal motivations (i.e., thinking of a woman as inferior, as property, as a sexual object) that lead to the crime, as opposed to thinking of the feminicidio as an isolated incident, a “crime of passion”, or the result of a few “bad apples”. Most common instances of feminicidio result from intimate partner violence (also known as domestic violence), sexual violence, murder in the name of “honor”, among others.

Feminicidio is an important topic throughout Latin America. While it is a problem that exists globally, throughout Latin America the rates of feminicidio are particularly high. Colombia is no exception – according to El Espectador, between 2009 and 2014 the rate of feminicidios in Colombia was cited to be as high as 4 per day.

During the day’s events in Medellin, the topic of feminicidio came up often. During the tribunal, various speakers discussed the problem of feminicidio in Colombia and specifically in Medellin, citing specific cases. During the march, many of the chants vehemently denounced feminicidio, expressing the simultaneous fear and rage of living in a society in which women fear death at the hands of known and unknown men. An example of a chant that was used throughout the protest:

Don Federico mató a su mujer

Es un feminicida machista también

La gente que pasaba nunca decía nada

¡No queremos más Federicos!

Lyrics courtesy of La Tremenda Revoltosa batucada feminista. This chant translates to: “Don Federico killed his wife / It’s a femicide and sexist as well / The people who passed by didn’t say a thing / We don’t want more Federicos!”

Turns out, this chant is a play on the lyrics of a popular children’s rhyme, which discusses Don Federico killing his wife (and subsequently chopping her up and cooking her.) The original rhyme about Don Federico exemplifies the normalized violence against women present in Colombia. The chant pushes back against this normalization of violence. After all, in order to change a culture of violence, it’s important to be critical of all of the ways in which violence manifests itself – be it the explicit ways, such as a feminicidio, or the implicit ways, such as a seemingly “innocent” children’s rhyme that falsely teaches children that violence against women is okay or normal.

Ni una menos / Vivas nos queremos

Ni una menos (“not one woman less”) and vivas nos queremos (“we want to live”) are two important hashtags used in feminist spaces throughout Latin America. The term ni una menos was popularized in Argentina in 2015. However, the term originally comes from Mexican poet and activist Susana Chávez, who was assassinated in 2011 after denouncing the feminicidios of hundreds of women in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

According to its official site, “Ni Una Menos es un grito colectivo contra la violencia machista. Surgió de la necesidad de decir ‘basta de femicidios’, porque en Argentina cada 30 horas asesinan a una mujer sólo por ser mujer.” This translates to: “‘Ni una menos’ is a collective shout against sexist violence. It arose from the necessity of saying ‘no more femicides’, because in Argentina every 30 hours a woman is killed, solely for being a woman.” Although the term was popularized in Argentina, it has swept throughout Latin America and is used in feminist spaces throughout the region to protest patriarchal violence and feminicidio. Vivas nos queremos is the partner term and hashtag to ni una menos. It means “we want to live”, the “we” specifically meaning “women”.

At the march in Medellin, one of the popular chants was the short and sweet:

Ni una menos

¡Vivas nos queremos!

“Basta ya de feminicidios!” (Femicides must stop now!)

Colombian armed conflict

The armed conflict in Colombia is a complex topic, and a key component in Colombian feminist discourse. I’m going to give the cliff notes version of the armed conflict and how it has impacted women’s rights in Colombia, but I also strongly encourage you to do some more research on the topic.

Colombia has essentially been in a civil war for about 50 years. The conflict began due to vast inequalities between Colombia’s wealthy elite and the poor working class. Guerrilla groups formed in the mid-1900’s as a means of defending the rights of poor farmers, who were continually exploited by wealthy landowners and a lack of government presence in more remote areas of the country. FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or “The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia”, in English) and other guerrilla groups initially gained popularity because of their claim to be defenders of the poor. Other players in the armed conflict include paramilitary groups (groups with military training that act independently of the State; in the case of Colombia, many paramilitary groups were formed and funded by drug lords), and the Colombian State (including the Colombian army), among others. The armed conflict in Colombia began in the 1960’s following a 10-year-long civil war called “La Violencia”, and remains an ongoing conflict in the country.

The Colombian armed conflict has marked a period of intense human rights violations, and those human rights violations have been particularly destructive to women. Women suffer disproportionately in any war or armed conflict, because rape is used as a weapon of war. In the Colombian armed conflict, sexual violence was used by all armed participants, including guerrilla groups, paramilitary organizations, and the Colombian state. While women throughout Colombia have been affected by the conflict, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian women have been disproportionately affected and represent a large percentage of the victims of conflict-related sexual violence in Colombia.

According to ABColombia:

Efforts have been made by women’s NGOs to document [conflict-related sexual violence in Colombia]; the most comprehensive study to date is that of the Campaign ‘Rape and Other Violence: Leave my Body out of the War’. Their study spans a nine year period (2001-2009) and finds that on average 54,410 women per year, 149 per day, or six women per hour, suffered from sexual violence in Colombia. These figures support the findings of the Constitutional Court that sexual violence constitutes a ‘systematic, habitual and generalised practice’ in the Colombian conflict.

Conflict-related sexual violence needs to be understood in its social and cultural context. In addition to patriarchal systems based on domination and gender discrimination, are other risk factors, such as social, political and economic marginalisation [sic]. These structural roots create a permissive context for the use of violence against women. Impunity for these crimes acts to reinforce, rather than challenge, these pre-existing norms and patterns of discrimination against women, both inside and outside of the conflict. Violence against women has been exacerbated by the conflict.

I highly recommend reading the report by ABColombia, titled “Colombia: Women, Conflict-Related Sexual Violence and the Peace Process” for more information on this topic, as well as the Conflict Profile from Women Under Siege.

In November 2016, the Colombian congress approved a peace deal between the Colombian government and FARC, which constitutes a victory for women’s rights in Colombia. The agreement includes language specifying the distinct need for women to be a part of the peace-building process, and the peace process signifies a decrease in conflict-related violence against women.

“Paren la guerra contra las mujeres, construyamos la paz” (Stop the war against women, let’s build peace)

Concluding thoughts / Notes on being an outsider in a liberation movement

I want to end this article on a slightly different note, and reflect for a moment on the space that I occupied on March 8th as a white, USian feminist at a Colombian feminist march and rally, as well as the implications of writing about Colombian feminism as a white, USian writer.

One recurring and striking thought that I had while at the event in Medellin was the fact that, although I was attending a march for women’s rights as a woman, I was very much an outsider while in this space. I think that this is an important idea to discuss, because I can see how any woman, any feminist, any person with a personal stake in the movement for women’s liberation, could assume that any feminist march inherently includes them. But this march in Medellin was about Colombian women and Colombian feminist issues, which are different from feminist issues in the United States. While we protest similar structural problems, such as patriarchal violence, racism, and homophobia, our present realities are different. Personally, I do not live in fear of displacement and sexual violence due to an armed conflict occurring in my town. I do not generally fear feminicidio. Ni una menos is a concept that is important to me… but it doesn’t necessarily represent me in my day to day life.

The struggle for women’s rights within my own culture is just as necessary and valid as it is in Colombia – but it also takes a different form in the United States. That’s why it was important for me to remember that I was marching in solidarity with the women and humans of Medellin. For anyone attending any sort of protest space in a liberation movement, I believe that it is important to understand when we are outsiders (or allies, or accomplices) to that movement, to avoid appropriating the movement as our own. We are there to support, to take direction from protest leaders, to respect the safe spaces that are being carved out, to add to the numbers, and to listen and learn.

Additionally: my discussing Colombian feminism and patriarchal violence within Colombia does not in any way mean that I am ignoring the critical systemic problems that exist in the United States related to gender and gender equality. The United States is a country of vast inequalities across all fronts, and we still face gender-related violence on a daily basis. I recognize that a lot of writing on gender issues in Latin America is fraught with racist “us versus them” language, pegging Latin America as hopelessly sexist while conveniently ignoring the sexism that permeates all aspects of life and culture in the United States. For more information on gender-related structural inequalities in the United States, I recommend my article on street harassment, as well as my Unlearning page (which is full of valuable resources, many of which focus on gender issues in the United States).

Finally, I want to add that this glossary just barely scratches the surface of the Colombian feminist movement and reflects my knowledge and research on the topic. Hopefully it helps you gain a basic understanding of the gender dynamics present in Colombia and the country’s fight for women’s rights!

How did you spend your March 8th? How is Colombian feminism similar or different to feminism in your country? What are some important terms and hashtags in the feminist spaces in your country? Let me know in the comments below!

2 comments

I definitely agree that the issues we face as feminists here in America are completely distinct from the women in Columbia or say Sudan, for instance. I I appreciate the respect and care you put into relaying this information accurately and thank you for filling the rest of us in!

Thank you for your very thoughtful comment, Jen 🙂 I’m glad that you found the post useful!