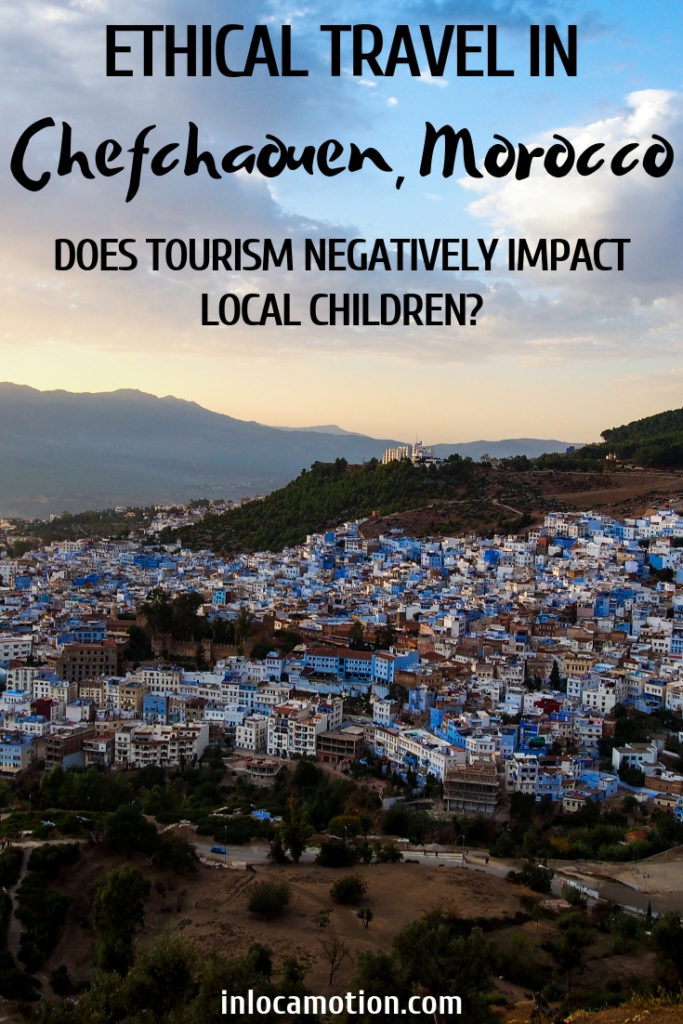

A stretch of cityscape in Chefchaouen, Morocco, seen from a rooftop terrace

Tourism in Morocco is booming, and it’s easy to see why. Morocco is a beautiful country with delicious food, rich history and culture, and a strong tourist infrastructure that makes travel there easier than you would think. One major tourist destination in Morocco is the picturesque city of Chefchaouen, “The Blue Pearl.” And let me tell you… Chefchaouen is pretty incredible, and worth the hype. I loved Chefchaouen and feel lucky to have had the opportunity to visit, but my time in the blue city did raise some important and uncomfortable questions about the multi-faceted impacts of tourism there. So buckle up, folks. I’ve got a narrative for you that will make you both smile and frown, all about Chefchaouen, interactions with local children, and big considerations about the impacts of tourism on this small, iconic Moroccan city.

Chefchaouen, Morocco: an introduction to the medina and the tourist experience

Chefchaouen (written شفشاون in Arabic and pronounced like shefSHAwon) is a gorgeous little city in northeastern Morocco. It’s about three hours southeast of Tangier, and about four hours north of Fes. It is extremely well-trodden on the tourist trail in Morocco, mainly because the attraction is the city itself: the old medina (essentially the old city) is painted entirely blue, so traversing its small network of winding streets is like stepping into another world. I felt happiness and excitement upon arrival in Chefchaouen, knowing that I had made it to a special place.

My time in Chefchaouen marked days three, four, and five of my Arabic language immersion. In Tangier, I had thrown myself headfirst into my studies of Arabic, re-familiarizing myself with words, phrases, and nuances of the language. Now in Chefchaouen, I had graduated from basic “survival Arabic” and was moving towards becoming conversational in the most rudimentary way possible. It was in Chefchaouen that I learned how to say phrases such as “Do you like to go hiking in the mountains?” or “I want some avocado juice.”

I loved Chefcahouen for the beauty of the city and the warmth of the friendships that I made there. However, I found walking around the city to be a jarring experience. I felt the weight of my presence in Chefchaouen, much heavier than anywhere else that I visited in Morocco. Perhaps it’s because the medina in Chaouen is so small, so there is much less anonymity there than in, say, Tangier’s medina. The medina is dominated by tourism, full of tourist shops, hotels, guesthouses, and restaurants. Even in the low season I saw many tourists, most of whom walked around with big cameras swinging from their necks to capture the beauty of the medina. I love photography (especially when traveling, to commemorate the special places that I visit), but I felt uncomfortable taking photos in Chefchaouen. It felt remarkably intrusive. I still took some photos but I tried to do so respectfully, only occasionally pulling my camera out of my bag.

As I walked around the city, many of the vendors would call out to me in Spanish, English, and sometimes French, to try to coax me into their shops to buy their artisanal rugs or leather satchels. I felt the sharp weight of contrasts between tourists and locals while in Chefchaouen, especially when it came to money. I felt guilty saying no to people trying to sell me things, especially seeing their dependence on tourism in the medina.

I explored these thoughts and more during my three days in Chefchaouen. But what really shook me was an interaction with a group of local children that occurred one evening, which was centered around something simple: reading. Allow me to explain…

A quiet, blue corner of Chefchaouen’s medina

Literature, language, and culture: an eye-opening interaction with local children in Chefchaouen’s medina

During my second day in Chefchaouen, I was wandering through the medina on my way back to my hostel. The sun was setting and the lights around the medina started to turn on, casting a soft glow of red across the sea of blue. As I ascended a blue staircase just a block away from my hostel, I stopped momentarily when something caught my eye that was bound to distract me: books.

One of many lovely blue doors in Chefchaouen

I love books. I love words and literature and stories. But I especially love books while traveling. I could spend hours browsing through foreign bookstores, picking up titles that I would never find in bookstores at home. And as a language learner, I know that reading is super important when it comes to advancing in a foreign language. So when this bookworm saw a pile of tomes on the staircase, I naturally had to go over and investigate.

The pile consisted mostly of books in Arabic and French. I flipped through some novels in Arabic, but I knew that they were way beyond my reading level. However, in one corner of the pile were a number of Arabic children’s books. Jackpot.

As I perused the pile, some bemused onlookers gestured to the books in French, as if to tell me, “You’re looking in the wrong language.” I shook my head and explained that I study Arabic. I then picked out two children’s books, purchased them, and carried them against my chest as I continued on my way back to the hostel.

Of course, I managed to take a wrong turn and I found myself walking along a slightly unfamiliar path. I paused, looking around in the dim evening light and wondering which way to turn, when two children ran up to me.

They couldn’t have been older than five, a little girl with a wide, toothy smile, and a boy even younger standing in her wake. The girl spoke to me in high-pitched, rapid Arabic. At first I was so confused; what did they want? But then the girl started pointing to the books.

I showed them the books. One had a big elephant on the cover. The girl took the elephant book and opened it up. She pointed to the first line of text and looked up at me with wide, challenging eyes. I glanced around, nervous. What is it about children that makes one feel like such a fraud? A group of men standing by one of the nearby shops watched us, amused. Two more little girls ran up to us, peering curiously over at the books.

I took the book and, holding it where the children could see the text and pictures, I attempted to read the first line out loud. What a struggle! Even with pronunciation markers in place, my reading in Arabic is slow… and my pronunciation is worse. I could feel my cheeks turn pink, my neck get hot. I read a few words before the girl interrupted me.

“ما إسمك؟” she asked me. What is your name?

“إسمي أليسا” I responded. My name is Alissa. “و أنت؟” And you?

“Aiza*,” she said, and then pointed determinedly at the script in the elephant book for the second time. I took a deep breath and proceeded to read.

After one sentence of what was probably the most butchered Arabic ever, Aiza impatiently took the book from my hands and led us over to some steps. She had me sit down next to her, the little boy on her other side. The other two girls settled on the step above us. Aiza was clearly the one in charge.

Aiza opened the book, pointed to the first line, and then proceeded to “read” to me. “Read” because even with my elementary Arabic, I could tell that she wasn’t actually reading, but rather inventing some rhyming gibberish while trailing her finger along the line of text. She let out high pitched giggles, the little boy next to her giggling as well. She occasionally nudged me, gesturing to the book as if to make sure my attention hadn’t wavered.

A blue staircase in Chefchaouen

I sat, perplexed, wondering whether they were giggling at the sheer absurdity of the sounds Aiza was making, or whether they were giggling because they were making fun of me. Maybe it was a combination of the two?

“Hola, hola!” The sound of a familiar word made me immediately look up. It was the older of the two girls on the step behind us, and she was looking right at me. She then glanced at Aiza and made the universal symbol for “crazy”. I grinned and shrugged, looking back down at the book in Aiza’s hands.

“Hola!” the girl said again. I looked back at her. It would appear that my name was now “Hola”. She pointed at the other book in my hands, and I handed it to her. She opened it up and proceeded to read, slowly and carefully, to the girl at her side.

I sat quietly, listening to the sounds of the children reading around me as day quickly turned into night. Aiza continued to flip through the book next to me, speaking in gibberish and intermittently giggling, while the older girl read on the step above us. “Hola!” she said to me when she finished the book. She then glanced pointedly at the book in Aiza’s hands as if to ask me for permission. I nodded, and the two girls exchanged books. The older girl opened up the elephant book and started reading.

Aiza, meanwhile, continued reading to me in gibberish. She lingered over one word, which I recognized. “عندما” I said, pointing to the word. The children burst out laughing. “!عندما! عندما” they corrected me. I couldn’t help but blush. “عندما” I repeated, though I was still met with giggles.

When the older girl finished reading the elephant book, she said “Hola!” and handed it back to me. “أنت تحبين الكتاب؟” I asked her. Do you like the book? She nodded with a small smile, glancing down at the floor.

By that point Aiza seemed to have tired of reading in gibberish. With the elephant book newly returned to our step, Aiza flipped it over to the back, where there were pictures of numerous animals. She pointed to the different animals, saying the name of each one. I repeated each name, the children immediately chiming in to correct my pronunciation. When we ran out of animals to name, Aiza asked me, “من أين أنت؟” Where are you from?

“أنا من أمريكا” I replied. I’m from America. I didn’t know how to say “United States” yet in Arabic, my preferred term for my country.

Aiza held her hands up to her face and made a clicking motion: the universal symbol for photography.

“Photo!” she said.

I immediately felt a nervous sinking of my stomach. Why were they asking me for a photo? “لا” I responded, shaking my head. No.

“لماذا؟” was the confused response from Aiza. Why? She pouted. “Photo!”

“لا، أنا لا أريد” No. I don’t want to.

Aiza eventually gave up, and I knew it was time to go home. “لازم أذهب إلى البيت” I told the children. I must go home. “…شكرا ل” I struggled. Thank you for… How did you say “reading with me” in Arabic? How about “the help”? In the end I just gestured to the books, smiled, and thanked them again. “ليلة سعيدة” Good night.

The children chimed “ليلة سعيدة” to me in return. I grinned and stood up, gave them a wave, and continued back down the path that I had begun on in search of my hostel.

Blue city by sunset

Reflections on the impacts of tourism in Chefchaouen

I’ve had an exceedingly difficult time analyzing this interaction with the children that night in Chefchaouen, mostly because I don’t know exactly what to think about it. They say you should be able to admit when you don’t understand something, so this is me admitting my confusion. I feel that it would be dishonest of me to solely detail this interaction with the children and leave you with a, “now, wasn’t that a nice moment?” Because yes, it was a nice moment, but it was also an unsettling moment, and I want to address that “unsettlingness” that I felt.

A mosque tucked into a corner of Chefchaouen’s medina

I think what was most jarring about this interaction with the children was that it represented, in a small but very honest way, what I observed to be the nature of the interactions between tourists and locals in Chefchaouen’s medina. There is a certain transactional nature to the interactions there, where the medina revolves around tourism and is sustained by tourist dollars. As a tourist there, I felt the conflict of wanting to spend money (and thus support), but at the same time I questioned whether or not the tourist presence there was actually positive in terms of the big picture of the city. Do the locals like tourists in their city, constantly traipsing around with their giant cameras, taking photos of their houses, streets, and doors? The presence of tourism inherently affects the culture and way of life of a place, but are those changes necessarily for the better?

I believe that there can be positive impacts of tourism, especially when tourism creates economic opportunities for folks who might not have those opportunities otherwise. However, I also believe that tourism is not necessarily positive for the host communities, especially in vulnerable places. There are real impacts to tourism: cultural and environmental degradation, worker exploitation, and more.

In Chefchaouen, I don’t know whether tourism is good or sustainable. And it’s too simplistic to argue the pros or cons of tourism from strictly an economic standpoint, when sustainability is threefold: cultural, environmental, and economic. All I know is that in Chefchaouen, I felt uncomfortable. Uncomfortable about the loudness of my presence, my foreignness, my wealth, my whiteness. Uncomfortable by the presence of my fellow tourists as well. And when confronted by a group of children interested in looking at some books, their transparency solidified this discomfort.

These children named me “hola” because they see their parents, siblings, and acquaintances throughout the town yell “hola” to foreigners, generally because “hola” is a word that we foreigners understand, that will grab our attention and hopefully begin a dialogue that will end with us spending money. I think that we tourists should do our part, economically, to support the places that we visit (and support conscientiously, so that our money goes into the pockets of locals, not foreigners). I also think that being called “Hola” by the locals is perfectly fine. But it did make me contemplate whether not not I should be in Chefchaouen in the first place. Was my presence there a positive one, or was it one that furthered this divide between locals and foreigners?

I have a lot of unknowns when it comes to this interaction, and I will continue to contemplate these unknowns while traveling and while at home. But in spite of the unknowns, I did walk away from the interaction with two solid thoughts:

Takeaway number one: I believe that I did the correct thing when I told Aiza that I would not take her photo. I don’t know why exactly she asked me for a photo. Perhaps it was because she wanted to see her face reflected back to her from my camera. Perhaps it was because she knows that other tourists already have and will continue to snap her photo, and that for tourists that there is value attached to her photo (regardless of whether she understands why or not). However, I am vehemently against taking photos of children, particularly when traveling. Plenty of (generally white) travelers go abroad to countries in the Global South, and take photos of black and brown children as if they were props for Facebook or Instagram. And race is relevant, because how often to people go to, say, England and take photos with the kids they meet to post on Insta? But for some reason, folks seem to think it’s okay to take photos of black and brown children. This is deplorable and tokenizing. A child can not properly consent to a photo. Travelers, be better.

And takeaway number two: I think that there is value in addressing the beauty of the moment that I experienced with these children as well. Yes, I feel that the interaction was complicated and loaded with layers of cultural nuance and geopolitics… but it was also, in a way, simple. It was a bunch of kids in Chefchaouen who got really excited to spend half an hour reading books with cartoon elephants and children on the covers. It was giggling, teasing, and inside jokes. It was playful and sweet. And while I walked away with my mind whirring, overly conscious and self-conscious of myself in space and time, I also felt that I had been given the gift of a moment: one in which I was able to witness the joy of children that resulted from reading a precious book.

*Not her real name

Have you been to Chefchaouen? How did you feel about it? What has been your experience traveling in areas dominated by tourism? Do you feel that tourism (in Morocco or elsewhere) negatively impacts local children? Let me know in the comments below!

18 comments

I started by being fascinated by the avocado juice (had a lot of it when I lived in Ethiopia and didn’t know it was anywhere else) and quickly moved on to being fascinated by your experience. I thought it was wonderful up until the ´hola’ bit and then, like you, I felt a wave of sadness. Isn´t it just so hard to try and figure this one out. I imagine though that those kids won´t forget you, you never know, they might talk for many years about the visitor who took the time to sit and read with them.

Avocado juice is kind of the best thing ever 😀 Haha. Anyway, more seriously, yes, there is a lot going on in this interaction, joy and sadness and more. I really like your optimistic take, though! In spite of feeling a bit weird about everything – the tourist presence in Chefchaouen, our impacts as tourists, etc – it is definitely nice to take a positive look at it in the sense that perhaps the kids did get something out of the interaction too! I sure hope so. Thank you so much for reading and for your thoughtful comment, Cassie 🙂

Sadly, I’ve heard a lot that many parts of Morocco are now a bit overwhelming for tourists… between the haggling and the street harassment, I guess a lot has changed since I was last there. But it looks like it’s still a beautiful country with rich culture. It’s cool that you’re learning Arabic and reading literature to connect deeper with the country! :)I hope to one day make my way to Chefchaouen/Northern Morocco. I suggest Ouzazarte and Zagora for your next explorations in Morocco. 🙂

I’d say I found it less overwhelming and more… contemplative, I guess. Like, I didn’t feel that people were hassling with respect to purchasing, more so that they were just trying to make a living and it’s hard to knock someone for that. It was more the overall inequalities between tourists and locals that made me question myself and whether or not my impact there was positive or not. But I definitely agree that it’s a very beautiful culture, and I loved the opportunity to travel there and learn Arabic. Thanks for the suggestions! I will keep in mind if I ever make it back there 🙂 Thank you so much for reading and commenting, Isabelle.

Really interesting story! I appreciated that you took the time to mull over your interaction with the kids. I’ve been in similar situations and it’s a strange place to be… Hard to know what to make of it all!

This post will definitely keep me thinking for days to come… So many little pieces to analyze and question about how tourism can affect what were once tiny, off the radar towns…

Thank you, Miranda! Yeah, there’s definitely a lot going on in interactions like these. I’m curious as to what similar situations you’ve been in and how you’ve responded/handled them? (Asking for a friend :P) Well, if in the coming days you think of anything else with respect to mine feel free to let me know! I feel like I’m still processing, even though it occurred quite a while ago! Thanks so much for reading and commenting 🙂

Fabulous article! It held my attention to the very end. Beautiful descriptions and analysis of your thoughts and feelings.

Thank you so much, Chantelle! Your kind words mean so much 🙂

Very interesting read. I really want to visit Chefchaouen and you have given a perspective on what it’s like there. Yes the impact of tourism on the local community has its pros and cons. I support your stance on taking photos of children. Good for you Alissa! Really like your writing style. Keep up the great work!

I really appreciate your kind and supportive words, Viola. Also that you get it about (not) taking photos of children – this one is such a big deal to me and I think it’s an important ethical consideration when traveling. If you ever make it to Chefchaouen I am curious to get your thoughts! Thank you so much for reading and commenting 🙂

I really personal narrative that captures the spirit of a place and its people. You really bring Aiza to life. I also had similar feelings about money and tourism when I was in Morocco (in Marrakech) so I really related to that part too. Thank you for sharing this story…

Definitely agreed about personal narrative! It’s my favorite form of travel writing because it’s so personal and raw… I’m not exactly the listicle kind of blogger, ya know!? 😀 Thank you very much for your positive feedback. And yes, Aiza was quite the vibrant person so I’m glad to hear that I did her justice! Thanks for reading and commenting, Frankie 🙂

That is such a gorgeous story. What lovely kids to be “reading” to you 😉

How are you doing with the Arabic now? I struggle with all the “h” sounds in Maltese, which is similar in some ways to Arabic.

Hey Katherine! Thanks for asking. It’s tricky. Right now I’m living in NYC, where there are plenty of Arabic speakers, yes, but I’m not interacting with the language on a daily basis like I was in Morocco. Because I’m still a beginner I think it’s also hard – I’m trying to find the right way to study on my own, or find a class, or something! And yes, the ‘h’ sounds in Arabic are tricky! There are three and they’re all slightly different. There are a few letters in Arabic that give me trouble. But I’m going to keep going with it – I’d love to be conversational, at least. How about you? Do you study Maltese or any other languages? Thanks for reading and commenting!

This is so beautiful. I love the way you write about your experiences – the awareness you have about yourself as a traveller as well. This was really great. Also, I’m just a sucker for travel and books – exploring real and fictional worlds, right?

Thank you so so much, Amy. Your comment put a big smile on my face. Thank you for reading and for taking the time to leave such a thoughtful comment! 🙂

Very interesting article. I’m reading your Tangier article next.

As for taking pictures of children and people- I’m nervous taking pictures of people in general, but that’s something I’m trying to overcome (It’s funny, my old preferred medium, drawing, was almost entirely people. And now I shoot stills and landscapes!) It’s “easier” to do things like that in foreign countries where you don’t speak the language because you’ll be awkward no matter what you do. On the other hand, tourists traveling off the path to places deep in, say, China get the same fetishized treatment, especially if they’re very tall or blue eyed or otherwise interesting. No one should take advantage of a foreign place or people, but everyone should have the discomfort of being a minority and slightly fetishized. It’s good for you- like trying to communicate in a new language!

Hi Mary, thank you so much for reading and taking the time to comment. There are a couple of things that I want to address here, since your comment brings up a lot of important points. The first, is that as a (white) traveler and photographer, especially in non-white countries, we need to be very careful when it comes to photography. If you want to take a photo of a person, always ask. Even if you don’t speak the language, you can learn how to ask “can I take your picture?” in the local language, as well as the responses of yes or no. I think that it’s incredibly important to ask, especially when you consider what a lot of these travelers do with these photos, which is share them on their blogs, Facebook pages, Instagram accounts, etc. Imagine if someone took a photo of you without your knowledge and threw it onto the internet for their thousands of followers to see… it’s a pretty vulnerable feeling. The fact that folks feel entitled to do this without even asking for permission really astounds me. Some cultures have different perceptions about photography, as well, so it’s also a part of being respectful and culturally-conscious. And as for children, I maintain my stance that we shouldn’t take their photos due to a lack of ability to properly consent to a photo.

I think that an important question that any photographer must ask themselves is, “why do I want to take this person’s photo in the first place?” Is is because they look different or strange? Also interesting to note is that when (white) travelers take photos of folks abroad, the subjects of the photos are almost always people of color (POC), and oftentimes Indigenous folks. What is the appeal of taking the photo of an Indigenous woman from Peru, let’s say, over a white woman from Norway? I think oftentimes travelers think that they need these sorts of photos to prove that they’ve had a more “authentic” travel experience, but at what cost? Tokenization is a part of racism; it sets whiteness as the default and everything else as, well, everything else (also known as the Other).

Which brings me your last point, about white/blue eyed folks experiencing their own tokenization in majority POC places. Yes, it’s true that this can happen, but the more important question is, “what is the impact of this happening?” Because the impact is really nothing, save for maybe that individual reflecting internally about how it feels to be treated differently because of looking different. However, when it comes to race and power on a global scale, there is no impact. The overall power and privilege that is awarded to white folks does not change. However, when white folks are the ones who are tokentizing/objectifying POC through photography, this (perhaps unintentional) racism keeps POC in a position of subordination to whiteness. In a way it’s a similar discussion related to why “reverse racism” isn’t a thing. (Here’s some more info on the myth of reverse racism if you’re interested: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/reverse-racism-isnt-a-thing_us_55d60a91e4b07addcb45da97)

So yes, while I think your last point is a good philosophical thing to consider in terms of, yes, it can be really humbling for white folks to be othered, since we are very rarely othered (which is what happened to me in this interaction with the children, when I was othered by them). But I think it’s important not to conflate white folks being othered with POC being othered, due to the systemic and global nature of racism.

Thank you for commenting and for opening up this dialogue. I am happy to discuss it further and provide more resources on the topic if you’re interested 🙂